Pacisco\Evaluative_Mechanism\Rationale

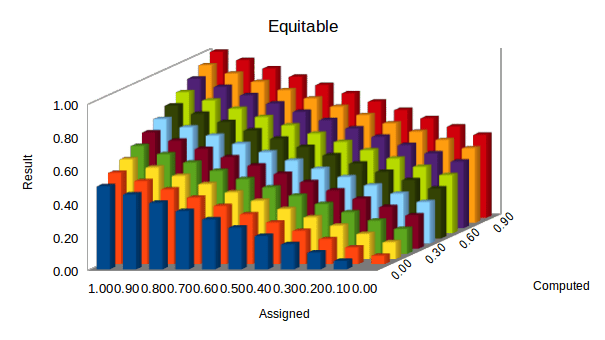

There follows a rationale for (or justification of) the Pacisco evaluation process. The steps in the process identified in the below diagram are each examined.

1: Prior ratings are assigned to cases by reviewers

1: Prior ratings are assigned to cases by reviewers

Pacisco relies on the understanding that, (in Joseph Joubert’s phrase) the aim of an argument or discussion should not be victory, but progress. Prior-ratings are intended to capture the reviewer’s degree of belief in the plausibility of the presented argument, irrespective of any current assessment of the validity of a particular claim. This demands substantial open-mindedness and a willingness to entertain the possibility that your current beliefs may be unsound (at least while interacting with Pacisco).

The reviewer’s rating should indicate their assessment of the plausibility of that particular case as a basis for establishing the validity of its associated claim. There are two steps to performing this evaluation:

- The reviewer should be asking themselves: supposing that the grounds and warrant were absolutely true, to what extent would this case substantiate its claim?

- The reviewer’s current evaluation of the plausibility of the grounds and warrant should be assessed.

The case’s awarded rating should take into account both 1 and 2.

For cases referencing external resources, the rating should reflect the support the resource actually gives the claim, as qualified by the warrant. Where this is difficult, perhaps because the warrant appears incorrect though the reference is good, the reviewer is at liberty to add a reference case with a more appropriately formulated warrant.

Pacisco does not require that reviewers rate all cases. Where a reviewer chooses not to rate a case, it will not be included in the calculation of the reviewers posterior rating of that claim. However, it will be included in the others posterior rating.

2: For Terminal Cases, the prior-rating becomes the post-rating

Terminal cases do not contain grounds and warrant. Types of terminal case in Pacisco are:

- Established fact

- Self-evidently true

- Self-evidently false

Cases marked as ‘established fact’ should be used when within the field of discussion, the claim is generally acknowledged to be true uncontroversially. This does not prevent other debaters rejecting this and adding additional cases. The reviewer’s rating should indicate their degree of belief that the claim is true. Higher ratings (even 1.0) may be expected.

For cases marked as self-evident, i.e. ‘self-evidently true’ and ‘self-evidently false’, the reviewer’s rating should indicate their degree of belief that the claim is in fact self-evident. Thus a reviewer may believe a claim to be absolutely true or false, but that this is not self-evident. In which case, they may add additional cases.

For terminal cases, as there is no further substantiation of the claim, the reviewers’ prior-ratings are treated as the effective rating of the case; the posterior-rating.

3: For Affirming and Rebutting Cases, the computed post-rating of the claims composing grounds and warrant are recursively computed

Affirming and rebutting cases contain grounds and warrant that are themselves composed of claims, with subordinate arguments.

Grounds may contain multiple claims joined using logical connectives. Each constituent claim must be evaluated to determine its ‘strength’. This is done recursively; i.e. this whole process is applied to each constituent claim and its subordinate arguments.

When multiple claims are joined logically (a compound proposition) the evaluation of the logical connectives is as described below.

3.1: Evaluation of Compound Propositions

To evaluate logical connectives in compound propositions (in the grounds of a case), Pacisco takes advantage of Cox’s Theorem to interpret logical connectives probabilistically. Essentially, conjunction (the ‘and’ connective) is defined as multiplication. In the formulae below, in the defined implementation (following :=), the operands are considered to be rational numbers, ranging between 0 and 1 inclusively.

The basis of the approach is to define the logical conjunction function as multiplication:

Conjunction (‘and’): x⋀y := x×y

Negation is defined as the reciprocal of the operand:

Negation (‘not’): ¬x := 1-x

Conjunction and negation are then used to define the remaining logical operators:

Disjunction (‘or’): x⋁y ≡ ¬(¬x⋀¬y) := 1-((1-x)×(1-y))

simplified to: y+x-x×y

Exclusive disjunction (‘either_or’): x⊻y ≡ ¬(x⋀y))⋀¬(¬x⋀¬y)

:= (1-(x×y))×(1-((1-x)×(1-y)))

Implication*: x⇒y ≡ ¬(x⋀¬y) := 1-(x×(1-y))

Equivalence*: x⇔y ≡ ¬(x⋀¬y)⋀¬(¬x⋀y) := (1-(x×(1-y)))×(1-((1-x)×y))

*Not currently available as connectives in the Pacisco editor.

The precedence of the operators is:

- Parenthesis

- Negation

- Conjunction

- Disjunction

- Exclusive-disjunction

- Implication

- Equivalence

Propositions are evaluated twice; once based on the individual debater’s ratings and secondly on the averaged ratings of all other debaters.

4: Ratings from grounds and warrant are combined conjunctively (And’ed) as the ‘strength’ of the case

In the Toulmin argumentation structure, grounds provide the data or evidence that the claim is based on, while the warrant provides the justification that the grounds are relevant to substantiation of the claim. Perhaps it would be appropriate for this distinction to be reflected in the way the strengths of these elements are combined to produce the strength of their case; something along the lines of inverting the Cox implication function. The strength of the case (the consequent) would be calculated given grounds as the antecedent and warrant the implication

Cox implication: i = 1-(a×(1-c)) may be rearranged to: c = (a+i-1)/a and a ≠ 0

However, this doesn’t work! From the implication truth table:

it can be seen that both a true and false antecedent can produce a true consequent. Thus deriving the consequent from the antecedent and implication produces an ambiguous result.

A pragmatic alternative (currently implemented) is to weight both grounds and warrant equally by combining them conjunctively (AND’ing them) to produce the strength of the case. Whilst this gives what appears to be a reasonable result, it lacks principled justification. Suggestions for improvement are welcome.

5: The case ‘strength’ is revised taking account of the prior-rating (damped) to produce the case post-rating.

This step essentially damps the revision of probability so that in Carl Sagan’s words: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” I.e., the posterior-rating of a case should be derived proportionately to its prior-rating; weak prior-opinion should be revised more radically than strong.

It would be rational to revise your assessment of the plausibility of a claim in the light of any revised plausibility of grounds and warrant in its cases. Pacisco does not require you to do this, but when evaluating subsidiary claims relevant to the case under consideration, it assumes that you would do this. It passes a plausibility rating up to the superordinate case after applying a revising function, taking as parameters the prior rating assigned to a claim by reviewers (a), and the computed case claim rating (c).

There is an arbitrariness about the revision function. Whilst the general essence of its effect should be as described above, there is no one way of achieving it. In Pacisco, four different versions of the revise function are currently implemented so the user can select the most appropriate. These functions are named: Rigid, Equitable, Flexible and none. They are described in detail below:

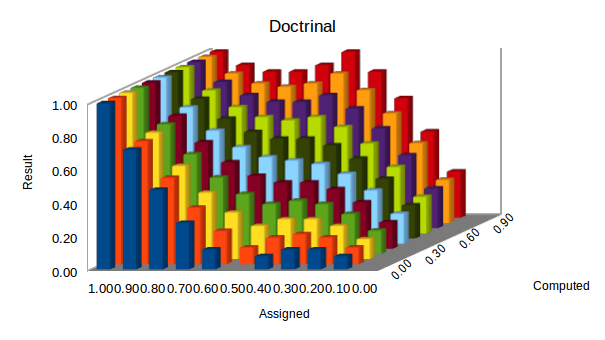

5.1: Rigid

Doctrinaire: based on and following fixed beliefs rather than considering practical problems. [Cambridge English Dictionary]

This revise function version has these attributes:

-

If the assigned rating (a) is categorical, i.e. 1 or 0, indicating unambiguously true or false respectively, then the function returns the assigned rating (a), the principle being that an absolute belief cannot be modified. A corollary is that absolute ratings should not be assigned lightly; they should be reserved for incontrovertible truths or falsities, generally arrived at by mathematical or logical processes.

-

If the assigned rating (a) is 0.5, indicating “undetermined” or ambivalence, then the function returns the computed rating (c). The principle here is that ambivalence is effectively no belief either way. Therefore the computed rating (c) should be adopted in its entirety as there is effectively no pre-existing rating to be modified.

-

If the assigned rating (a) is between 1 and 0.5, or 0.5 and 0, both exclusively, then the function returns a compromise between assigned (a) and computed (c).

The Rigid function is implemented as:

a + (((0.5 – |a – 0.5|)×(c – a))×2)

Its behaviour is illustrated in the column chart below:

5.2: Averaging

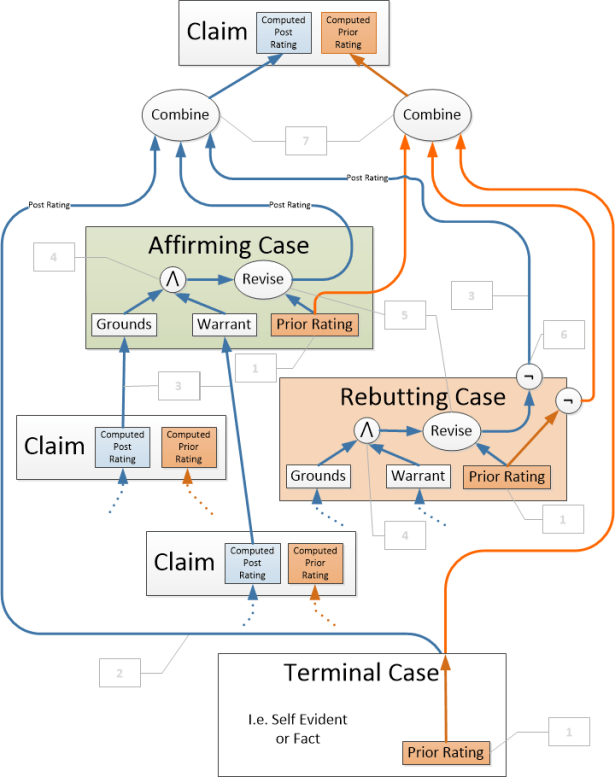

Equitable: treating everyone fairly and in the same way. [Cambridge English Dictionary]

This revise function version has these attributes:

- Categorical (1 and 0) and undetermined (0.5) ratings are treated no differently than any other valid rating. So categorical prior (assigned ‘a’) ratings do not prevent intermediate values being assigned as post ratings.

- Post values are evenly distributed with no bias in favour of the prior rating.

The Equitable function is implemented as:

(a + c) / 2

It is essentially the mean of the assigned and computed ratings. Its behaviour is illustrated in the column chart below:

5.3: Flexible

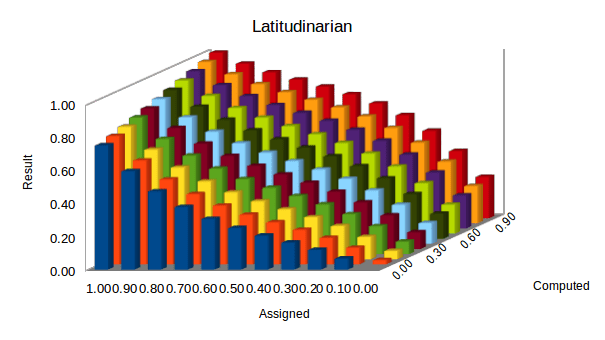

Latitudinarian: not insisting on strict conformity to a particular doctrine or standard. [Merriam-Webster English Dictionary]

This revise function version has these attributes:

- Categorical (1 and 0) and undetermined (0.5) ratings are treated no differently than any other valid rating. So categorical prior (assigned ‘a’) ratings do not prevent intermediate values being assigned as post ratings.

- Post values are calculated with a bias in favour of the prior rating.

The Flexible function is implemented as:

a + ((0.5 – |a – 0.5|2) × (c – a))

Its behaviour is illustrated in the column chart below:

Flexible is the default revision function.

Flexible is the default revision function.

5.4: None

The prior rating is ignored and the post rating becomes the computed rating.

This may be a useful setting (perhaps together with combination algorithm setting of Extreme) for exploring the workings of Pacisco. However, as an actual evaluation of the argument it is of dubious utility.

6: For rebutting cases, both the prior-rating and post-rating are negated.

To convey the intention of rebuttal, the Cox negation function is applied to both the computed and assigned case-ratings.

7: For all cases, prior-ratings and post-ratings are separately combined.

Some collaborative argumentation systems establish the strength of claims by voting among the reviewers. This may simply compare the relative numbers of ‘likes’ between cases or claims, or where relative degrees of assent are recorded, averages may be compared. This clearly has value in establishing the distribution and strength of opinion within a population. However it incorporates dubious epistemological principles; that truth is determined by popular opinion; and that what is important is rhetorical victory. The purpose of rating in Pacisco however, is to draw attention to inconsistency in argument, together with points of significant controversy.

In line with this, Pacisco’s method of establishing the rating of a claim is implemented at three different selectable algorithms named as: Disjunction, Extreme and Mean. These are described below:

7.1 Disjunction

The rating of a claim is computed by applying the Cox disjunction operation; i.e. or’ing all of its cases. This is the most logically correct approach and is the default setting. However there are issues when interpreting the result.

Principally, the effect of applying the Cox disjunction function is to potentially inflate the overall rating through the addition of multiple weak or even rebutting cases. The disjunction function is implemented as:

1-((1-p)×(1-q))

It always produces a result that is greater than its largest operand, except in the case of one operand being zero when it is equal to the largest operand. So the addition of rebutting cases can actually increase the rating of a claim. Intuitively a rebutting rating (i.e. less than 0.5) still assigns some probability to the claim; the disjunction function collects this into its result.

The remaining two algorithms address this issue.

7.2 Extreme

This algorithm identifies the strongest case, which may be either affirming or rebutting. This is taken to be the case with the most extreme rating (i.e. closest to 0 or 1); so the strongest case may refute the claim. When there are equally extreme ratings for supporting and rebutting cases, they ‘cancel out’ and 0.5 (undetermined) is returned.

However this approach does not acknowledge the quantity of cases made for and against a claim. In some domains of discussion it may be appropriate to acknowledge that there are more, though weaker supporting cases than rebuttals or vice versa (e.g. in policy making); the mass of weaker support outweighs the more substantial but scant opposition cases. The next algorithm, Mean addresses this.

7.3 Mean

A combined rating of a claim is computed by averaging the ratings of all its cases. Thus rebutting cases actually reduce the overall rating.

Other methods of producing a ‘combined’ rating are possible though not currently implemented.